The Politics of Data Centers Have Gone Local

And how advocates should approach their engagement

Last week, the Chandler, Arizona city council voted unanimously to deny a hotly-contested proposed data center project. The high-profile nature of this vote wasn’t because it was a novel issue, but because it could be a harbinger for AI politics.

In fact, local cities and municipalities have already been facing proposals like this for the past few years, and 2025 has seen largely one-sided action against this core part of the AI infrastructure buildout.

In August, another Arizona city voted against a large data center project outside of Tucson.

In April, Loudoun County, VA (colloquially known as “data center alley”) voted to impose additional hurdles to approve data centers.

Last year, the entire city council of Warrenton, VA was voted out of office after initially supporting a data center project. That project is now on ice.

Other city councils from Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, and Illinois have taken similar actions.

And of course, statewide elections in Virginia saw data centers and electricity prices emerge as a key campaign issue.

In short, deliberations that were once exclusively isolated amongst economic development and zoning offices have now expanded into a much larger political debate around housing, energy, and water concerns—with the tide now appearing to turn against data centers.

What To Make of This

This has all the makings of a potent grassroots issue that Washington won’t recognize until it’s too late.

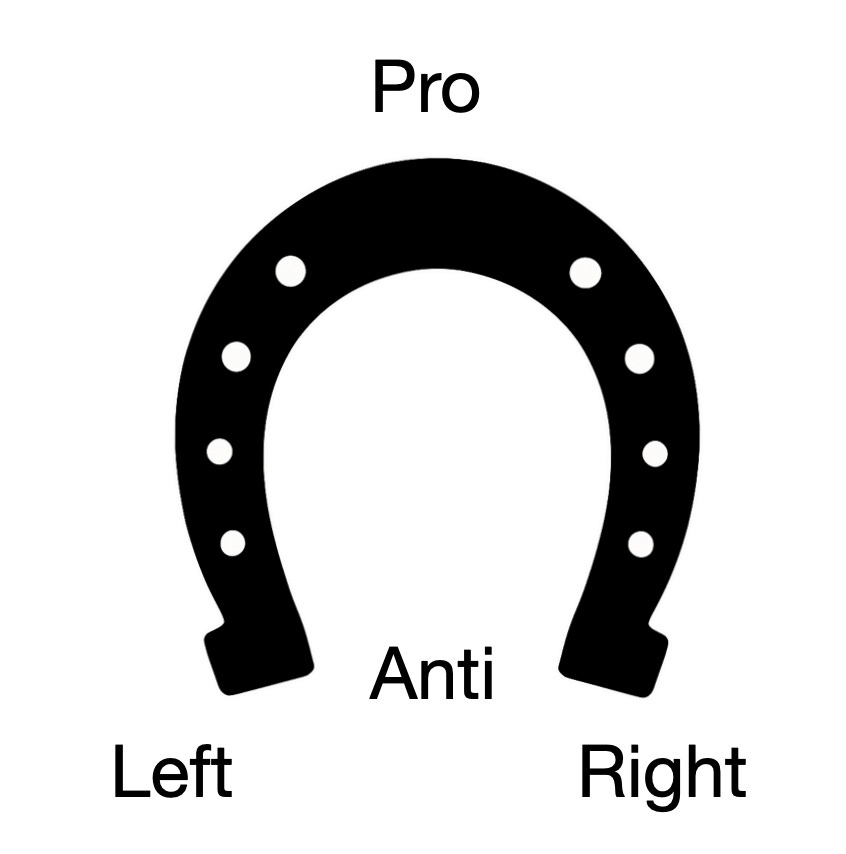

For starters, it’s obvious that given the Trump administration’s open embrace of AI, Democrats would try to stoke anti-AI sentiment. But while it might be tempting to cast aside these efforts as simply Democrat-led, many of these local disputes have produced strange bedfellows—a classic “horseshoe” coalition of the right and left having the same position, albeit for different reasons.

Back in Arizona, for example, former Chandler councilman and current member of the Arizona House, Republican Jeff Weninger, opposed the project. But Rep. Weninger isn’t some luddite. He was chairman of the Commerce Committee and is one of the most tech-forward legislators in the state. He told us his position was largely based on the project’s proximity to a neighborhood that already has registered numerous noise complaints against data centers. His opposition highlights the complexities that developers and advocates must navigate with these projects.

Our Take

Unlike setting a federal framework around AI regulation, earning support for data center construction isn’t primarily a policy challenge. It’s a political one.

With the political fundamentals of AI already on shaky ground (even advocates agree that industry hasn’t done a good enough job explaining the benefits), engaging communities around the physical infrastructure needed for AI requires a far more deliberate approach. These fights are not won with white papers or macro arguments. They are won locally, through trust, process, and presence.

Here are a few principles that should guide that engagement:

1. The most powerful political skill is listening.

Too often, public debates begin with data points in hand and a desire to “win” the argument. That instinct is counterproductive. Listen first. Hear what residents are actually saying—about noise, traffic, water use, or quality of life. Talk last. Listening is how you identify real concerns, proxy arguments, and which audiences are genuinely persuadable.

2. Engage in multiple settings—not just town halls.

Relying solely on city council meetings and public hearings creates a charged, performative environment that builds toward a single “brace for impact” moment, often amplified on social media. Smaller listening sessions, one-on-one conversations, site visits, and informal community gatherings create dialogue instead of theater—and produce far more useful feedback.

3. Be persistently present.

An ALFA reader recently noted that opposition to data centers is growing in their Tennessee community, while proponents have largely buried their heads in the sand. That absence is politically fatal. When supporters fail to show up early and often, opponents define the project by default. Once those narratives harden, facts matter far less.

4. Explain why the technology—and its infrastructure—matters locally.

Abstract national arguments won’t carry the day. “The race against China” is unlikely to resonate. But a more reliable electric grid, better-funded schools, workforce training, or long-term economic stability might. People don’t oppose data centers because they dislike technology; they oppose projects that feel imposed, extractive, or irrelevant to daily life.

One Final Thought

Axios co-founder and CEO Jim VandeHei recently observed

We’ve entered the post-news era. Your reality—how you see the world—is no longer defined by ‘the news.’ Instead, it’s shaped by the videos you watch, the podcasts you listen to, the people you follow on social media and know in person.

As it applies to data centers, winning support requires less persuasion and more presence—listening early, showing up consistently, and grounding abstract technology in tangible local value. Citizens’ realities are shaped long before a zoning vote—through neighborhood Facebook groups, local podcasts, church conversations, and word of mouth. Right now, in many communities, only opponents are showing up in those spaces.

As the saying goes, “all battles are won before they are fought.” And not by who has the better argument, but by who earns the community’s trust before the first vote is ever taken.